The Social Baseline Theory

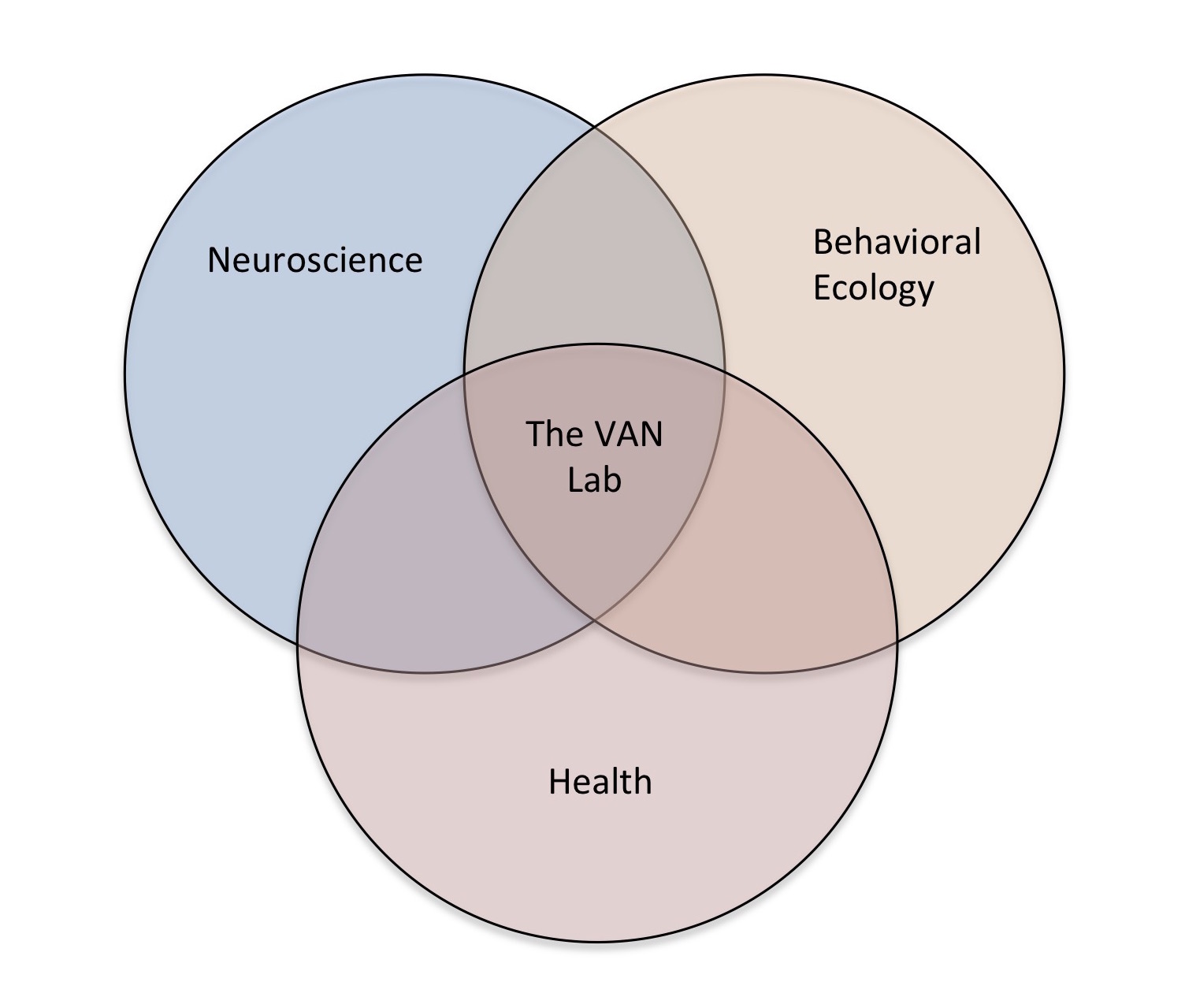

High quality social relationships correspond with longer, happier, and healthier lives — facts that hold true, as far as anyone knows, regardless of geography or culture. Although social relationships have been linked to health for decades (if not millennia), the mechanisms of this link remain speculative. Here we describe Social Baseline Theory (SBT), a perspective that integrates the study of social relationships with principles of attachment, behavioral ecology, cognitive neuroscience, and perception science.

According to SBT, the human brain assumes proximity to social resources — resources that comprise the intrinsically social environment to which it is adapted. Put another way, the human brain expects access to relation- ships characterized by interdependence, shared goals, and joint attention. Violations of this expectation increase cognitive and physiological effort as the brain perceives fewer available resources and prepares the body to either conserve or more heavily invest its own energy This increase in cognitive and physiological effort is frequently accompanied by distress, both acute and chronic, with all the negative sequelae for health and well being that implies. Thus, the first sense in which SBT refers to a social baseline has to do with the default and intrinsically social ecology the brain expects to function within.

But reference to the social baseline also has methodological meaning. In functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research, a standard convention is to compare an experimental treatment to a ‘resting baseline’ character- ized by simply lying alone in the scanner. This conven- tion is predicated on the reasonable assumption that experimental treatments present stimuli otherwise absent from the sensorium while participants are alone. But inspection of brain activity in several studies — elaborated on below — now suggests the brain responds to being alone as if sensory stimuli have been added, not taken away. That is, the brain looks more ‘at rest’ when social resources are obviously available. This presents a puzzle potentially resolvable by considering proximity to a familiar other the brain’s true ‘baseline’ state, and being alone as more like an experimental treatment — a context that adds perceived work for the brain to do.

Social relationships decrease the predicted cost of the environment

Abundant evidence suggests that the likelihood of a behavior is optimized by calculating its metabolic cost against its perceived payoff, given prevailing personal bioenergetic resources. For example, human subjects tend to view hills as steeper, and distances as further away, if fatigued, sleepy, physically less fit, stressed, wearing a heavy backpack, or even simply in a low mood. It is thought that these perceptual shifts regulate the motivation to walk up hills. Steeper hills require higher payoffs to justify the bioenergetic investment associated with climbing them, and diminished personal resources cause hills to look steeper.

At its simplest, SBT suggests that proximity to social resources decreases the cost of climbing both the literal and figurative hills we face, because the brain construes social resources as bioenergetic resources, much like oxygen or glucose. Indeed, evidence suggests that hills literally appear less steep when standing next to a friend. Moreover, socially isolated individuals consume more sugar, even after adjusting for body mass index, weight related self-image, depression, physical activity, educational level, age and income. To the human brain, social and metabolic resources are treated almost interchangeably.

Risk, effort, and the expanded self

SBT describes at least two reasons for the regulation of perception and effort by social proximity: risk distribution and load sharing. Colloquially speaking, risk distribution is simply safety in numbers. In a vast array of species, individual threat vigilance decreases as group size increases. But social species also benefit from load sharing, which entails not only the distribution of risk, but also the distribution of effort applied to shared goals, often to great mutual advantage. Load sharing is strongly facilitated by familiarity, preference, joint attention, and trust — in short, by relationships. The distribution of risk and effort applies across levels of analysis, including neural processing.

Although the brain is highly responsive to perceived threat, even simple handholding can substantially attenuate threat responses. These effects are potentiated by higher relationship quality, intimacy, and higher perceived mutuality. Individuals who experienced more maternal support behavior and higher neighborhood social capital in childhood are more receptive to social regulation as adults. And a marital therapy designed to target the quality of attachment bonds increases receptivity to the social regulation of threat processing as well.

Critically, the likeliest mechanisms linking social support to diminished threat responding — regulatory circuits within the prefrontal cortex — are not more activated by support provision as originally hypothesized, but less so. During supportive handholding in particular, the threat responsive brain appears to return to a baseline state of relative calm, suggesting the difference is attributable less to the activation of regulatory circuitry and more to a decrease in perceived demand associated with the threat, a decrease proportional to the increase in resources brought to bear by the relational partner.

An important question then is how the brain perceives proximity to a relational partner as an increase in bioenergetic resources. SBT suggests the answer may lie in how the brain encodes what we subjectively experience as the self. Many theorists have suggested that the self is ‘expanded’ by relationships with others. This may be literally true at the neural level. For example, the brain encodes threats directed at familiar others very similarly to how it encodes threats directed at the self — but no such similarity obtains for strangers. Representing relational partners as extensions or aspects of the self could effectively yield bioenergetic resources by influencing how the brain budgets the resources immediately at its disposal. If the relational partner can be counted on to meet all or part of an environmental demand, one’s own resources can either be conserved or devoted to other problems as if personal bioenergetic resources were literally increased. This could explain how the brain construes resources available to relational partners as resources available to the self. Indeed, it suggests that attachment may reflect a neural (and conceptual) conflation of self and other. We see this as likely.

Relationship loss increases the predicted cost of the environment

We have suggested that an important aspect of SBT is the neural integration of self and other, consistent with self-expansion views of close relationships. Evidence supporting shared neural representations of self and other informs our understanding of how intact relationships economize behavior, and suggests new questions about relationship loss. Many view relationship loss as a loss of self. According to SBT, this diminishment of the self is more literal than figurative. Framed in experimental terms, the end of a relationship represents a move away from our social baseline to an alone condition. As a result, threats should look more threatening, the environment should feel more burdensome, the proverbial hills of life should steepen. This all suggests first that becoming unattached from a former partner entails re-defining one’s sense of self as independent of that partner and facing costly new environmental demands as a result. Second, the extent to which this ungrafting of the self and other is successful should at least partially mediate recovery from a loss experience.

Non-marital romantic breakups are associated with immediate and persistent decreases in self-concept clarity, and recovery of an independent sense of self prospectively predicts increased psychological wellbeing following a breakup. These findings raise additional questions. How quickly do people incorporate new social resources back into a damaged self-concept? Is the self-regulatory load associated with loss in fact correlated with the degree of self-concept disturbance? There is evidence, for example, that people who score high in attachment avoidance may be protected against the self- concept disturbances associated with relationship loss, but only to the extent that they can successfully regulate their own emotions while thinking about their ex-partner. Can new social resources help here as well? Going forward, a critical question for (and informed by) SBT concerns the extent to which self-regulatory demands — and capabilities — change as people transition from partnered contexts to those that provide fewer immediate social resources.

Tentative conclusions

SBT suggests (1) that the human brain assumes proximity to social relationships characterized by shared goals, interdependence, and trust; and that the human brain construes social relationships as bioenergetic resources, encoding others as part of the self. This allows humans to, in effect, outsource everything from probabilistic risk to threat vigilance, emotional responding, and a host of other demanding neural and behavioral activities. Thus, proximity to social resources regulates our propensity for engaging in neural and behavioral work, with implications for how we think, act and feel. When social resources are available, we are expanded, larger, more capable of meeting environmental demands. When social resources are absent, unreliable, or lost, our sense of self is diminished, along with both our objective and subjective efficacy.

If ultimately true, SBT holds implications not only for our understanding of conceptual perspectives like attachment theory, but also for research methodology in psychology and related disciplines. We acknowledge for example that SBT and attachment theory are strikingly similar, and do not propose that one invalidates or sup- plants the other. Rather, SBT describes a more generalized set of neural and ecological processes — organizational principles — that do not necessarily contradict attachment theory, but may subsume it. One exception may be the question of ‘attachment figures’ per se, about which SBT is largely silent, at least as regards qualitative differences across types of relation- ships. Another concerns putative attachment styles, interpreted within SBT as prior probabilities in a Bayesian process of predicting the availability of social resources.

Interestingly, viewing social proximity as a baseline assumption of the human brain carries with it some potential methodological implications, at least insofar as most participants in psychological research are tested in relative isolation. This may not be a serious problem, but SBT does at least invite the possibility that a large range of cognitive, perceptual, emotional, developmental and clinical phenomena manifest differently — and perhaps more generalizably — in the presence of trusted and familiar others. Increasing evidence suggests to us that this may indeed be the case.

With its emphasis on the optimization of resources and effort, SBT also offers novel ways to think about social relationships in the context of clinical interventions. Recent interpersonal approaches to psychotherapy suggest, for example, that couple-level interventions are not

only efficacious for treating relationship distress, but also for leveraging social resources in our understanding and treatment of, for example, borderline personality disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, heart disease, the suffering associated with cancer, and the emotional burden of caring for chronically ill children. This and related work suggest real potential for the application of social resources in prevention and treatment of a wide array of medical and psychological difficulties. Indeed, we are optimistic that our understanding of the nature, function, and centrality of social relationships for human flourishing is steeply on the rise, and we look forward to many fruitful applications of this knowledge in the coming years.

— James Coan and David Sbarra